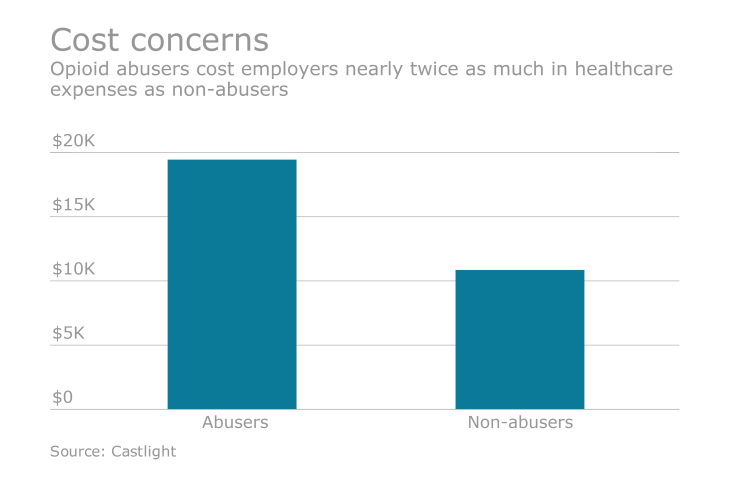

With new data from Castlight Health Inc. revealing that opioid abusers cost employers nearly twice as much ($19,450) in medical expenses on average annually than non-abusers ($10,853), the onus is shifting to employers to implement health plan designs that will help to address the opioid epidemic.

The study, based on anonymous information covering nearly one million Americans who use the Castlight’s health benefits platform, also shows that nearly one out of three opioid prescriptions subsidized by U.S. employers is being abused. Medications relieving pain that fall within this class include Vicodin, OxyContin, Percocet, codeine and other related drugs.

“This crisis is having a significant impact on the nation’s employers, both in the form of direct and indirect costs,” says Kristin Torres Mowat, senior vice president at Castlight. “From higher spending on healthcare, to lost productivity, to the dangers associated with employees abusing medications in the workplace – these are aspects of the crisis that are too often overlooked in the current discussion.”

These findings are consistent with

Keith Rosenblum, a senior risk consultant at Lockton and author of the report, believes that medical over-diagnosis is the underlying problem. “Physicians are identifying conditions that are more serious than they really are and not practicing evidence-based medicine,” he says. “We are using opioids as a de facto solution to treat chronic pain when 75% to 85% of patients have an actual mental health or psychosocial overlay.”

In fact, in a recent analysis of the role employers can take to manage opioid use in the workplace, the

Nevertheless, Rosenblum notes that approximately one-third of workers off with new low-back pain injuries receive opioids during the first six weeks after injury and usually on the first visit. “Yet the literature shows that receiving two opioid prescriptions during this early time frame is associated with the doubling of the risk of disability at one year,” he says.

Recognizing the financial impact of opioids on workers’ compensation claims, 14 states either have adopted or are working on closed drug formularies which substantially control unnecessary prescribing of narcotics treating acute and chronic pain. Closed formularies essentially use evidence-based medicine to identify the prescription drugs that should be allowed for certain injuries. All other medications must go through a pre-authorization process.

Texas was an early adopter of prior approvals for about 150 drugs dubbed ‘N-drugs’ that are not recommended for injured workers in workers’ compensation cases. In July 2013, the Texas Division of Workers’ Compensation reported that since the new rules were adopted, N-drug prescribing was reduced by 74% among newer claims. In addition, the total spent on N-drugs for those claims also dropped 82% to less than $800,000 in 2010.

More recently, a California study suggested that the California workers’ compensation system could save between $124 million and $429 million annually by adopting similar restrictions. As a result, California Governor Jerry Brown signed A.B. 1124 that will create an updated formulary for the state’s injured workers effective January 2017.

But improper opioid use can be a problem for employers even where employees are not covered by workers’ compensation. “The latest stats are that about 260 million opioid scripts have been written in the last year. Many people taking these drugs are still employed so it’s going to affect their cognitive abilities and judgment both when they are on the job and outside of work,” Rosenblum says.

“This crisis is having a significant impact on the nation’s employers, both in the form of direct and indirect costs.”

What can employers do? The NSC suggests that there are opportunities for benefit plan sponsors to leverage the technology of their pharmacy benefit managers to obtain data about their opioid spend and ensure there are system flags for repeated “too early” refills, high daily dose levels and duration of therapy.

In addition, the

1. Partner with prescription drug and health plan providers to help gate-keep, monitor and intervene on the use of these prescription drugs.

2. Review the company’s drug-free workplace policy to protect employees and reduce liability.

3. Ensure that any employee drug testing program includes testing for the most commonly prescribed opioid painkiller drugs.

4. Remind employees of confidential help available through an employee assistance program.

5. Educate employees about safe storage of these medications, proper disposal and risks of sharing these powerful drugs.

“Furthermore, where a patient is experiencing chronic pain and no specific underlying condition has been identified, opioids are generally not the answer,” says Rosenblum. “Physicians should refer the patient for a health and behavioral assessment to determine if there is any underlying psychosocial or mental health problem.”