Kate Nicholson was curled up under her desk, writhing in pain, when her spine caught fire. A previous operation to correct the effects of endometriosis caused the nerves in her back to grow hypersensitive; droplets of water in the shower felt like needles piercing her skin. Soon, she’d be unable to walk.

Determined to continue working as a civil rights attorney at the Justice Department, Nicholson refused to take prescription opioids for her pain, convinced they would compromise her “mental clarity and sharpness.” She wanted to try acupuncture to manage her pain without prescription drugs, but her employer-sponsored health insurance wouldn’t cover visits — it would only pay for the drugs. If she wanted alternative pain management, she’d have to pay for it herself.

“I didn’t understand why healthy, non-invasive therapies weren’t covered; it’s ridiculous,” she says. “I was a privileged patient; I had a decent income, so I was able to pay out-of-pocket for alternative care. Not everyone can do that.”

Nicholson isn’t alone in her problems when it comes to pain management coverage.

According to the latest figures from the Society for Human Resource Management, only 6% of employers provide “alternative/complementary medical coverage” in their employee plans. Alternative coverage includes therapies like massage, yoga and biofeedback (a combination of electrical brain activity data and mindfulness techniques.)

The number is down from 17% of employers offering the benefit in the previous two years.

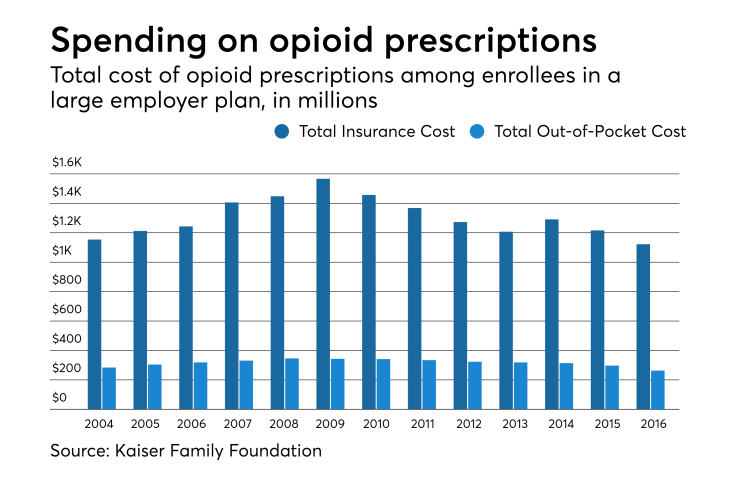

At the same time, opioid addiction has soared. More than 130 Americans die of opioid overdoses every day, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Employers everywhere are dealing with increased “costs of healthcare, lost productivity, addiction treatment and criminal justice involvement,” the CDC says. The organization estimates the opioid epidemic costs the U.S. economy $78.5 billion a year.

So why aren’t employers looking more at alternatives that could prevent addiction within their workforce?

“Employers are always concerned about opening the floodgate to things that might seem frivolous or unnecessary, but in light of concerns over the opioid epidemic we need to find other less addictive ways to manage their issues and pain,” says Mike Thompson, president and CEO of the National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions, an employer group.

The Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force — a division of the Department of Health and Human Services — issued a report in May with a list of practices that can be used to manage chronic pain as an alternative to opioids.

A few of these treatments include chiropractic care, massage therapy, acupuncture, yoga and spiritual practices like meditation.

That task force was formed to address acute and chronic pain to address the ongoing opioid crisis that touched 1.7 million Americans in 2017, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

“Complementary and integrative health, including treatment modalities such as acupuncture, massage, movement therapies (e.g., yoga, tai chi), and spirituality, should be considered when clinically indicated,” the HHS report says.

TRUE COST OF ADDICTION

The Department of Health and Human Services recognizes patients with severe diseases, like cancer and sickle cell anemia, have to rely on opioids for pain management. But using them to mask temporary pain — both physical and mental — can have serious consequences.

Gary Mendell spent decades building HEI Hotels & Resorts — a multibillion-dollar hotel empire. During this time, Mendell was also fighting to save his son’s life.

For years, Mendell’s son, Brian, struggled with addiction to prescription painkillers. At the age of 26 — after participating in many remission programs — Brian celebrated a full year of sobriety. Brian’s family thought he was over the hurdle; he wasn’t. Not long after celebrating a drug-free year, Brian took his own life.

“In his loving and compassionate note to our family, [Brian] condemned the treatment system for its lack of integrity,” Mendell says in an online memorial dedicated to his son. “And although he did not state it explicitly, I believe he also felt enormous shame and guilt that tore him apart inside.”

Mendell — whose organization, Shatterproof, helped pass 16 laws in 14 states to limit access to prescription opioids — says while third-party administrators are making strides, the methods they use to compensate medical professionals is largely to blame for the epidemic.

Insurance companies often limit the amount patients can spend on pain management treatments after undergoing a medical procedure, like surgery. In many cases, opioids tend to be the cheaper option compared to alternative treatments and non-opiate drugs.

“Take someone who has a minor surgery. There’s a fixed price for the surgery, and the fixed price includes the surgery itself and pain management,” Mendell says. “That doesn’t leave you with much money to spend on other treatments. As a doctor, you can prescribe a generic opioid for $50, versus a branded form that’s not an opioid that may cost a couple hundred dollars.”

Mendell expects four more laws limiting access to opioids to pass this year. In the meantime, Mendell and Shatterproof have curated six five-minute videos for a program called Just5 to help educate employers and their workforce about how they can do their part to prevent addiction.

General Electric and Hartford, an insurance company, are among Just5’s users.

“Employers really need to take initiative and educate their workers about addiction,” Mendell says. “People are often afraid to come forward because of how it’ll affect work; this is your chance to be their advocate.”

EMBRACING ALTERNATIVES

Although adoption of pain alternatives are rare, some employers are embracing the alternatives with open arms. Metro Nashville Public Schools — a school district teaching more than 85,000 students — offers its staff and their families chiropractic care and acupuncture at a private clinic on the district office campus. School administrators say providing access to these services significantly lowered prescription painkiller usage in their workforce.

“My data shows opioid use in our district is almost nonexistent,” says David Hines, director of benefits at Metro Nashville Public Schools. “People love visiting the chiro and physical therapist; we’re getting some great outcomes.”

Hines estimates there are about 380 chiropractic and acupuncture visits at the district clinic per month, which he says is great because the district wants its employees to take advantage of the services. And to make care more accessible, Hines says the district eliminated all copays for chiropractic and acupuncture visits; employees pay nothing out-of-pocket at each appointment.

“Remove the barrier. Let’s get beyond the cost of bad health and focus on providing a means to good health,” Hines says. “It makes more sense to heal people than to medicate folks. That’s where our focus is, and it seems to be working.”

The 26,000 square foot clinic was erected two years ago, and includes an onsite pharmacy, fitness center and conference rooms. Hines says it costs around $62 per member a month to run the clinic, which is overseen by third-party administrator Cigna.

Cigna covers chiropractic care, and included acupuncture to its lineup last year.

“Cigna offers programs for those who want to pursue those types of interventions,” says Dave Mino, national medical director at Cigna. “We feel a combo of acupuncture and physical therapy can help patients become more self-sufficient and lead to lower use of opioids.”

Chiropractic care and acupuncture are seeing more employer support than other alternative treatments; 80% of company health plans covered chiropractor visits, while 47% funded acupuncture, according to the SHRM survey.

Chronic pain frequently plagues the musculoskeletal system — areas where muscle and bone connect — because that’s where nerves gather, Mino says. The spine is especially sensitive because it’s directly connected to the nervous system. Acupuncture and chiropractic care are adept at addressing pain in these areas for different reasons, he says.

In the case of acupuncture, sliverlike, sterile needles, when inserted, stimulate the nerves and send signals to the brain to produce endorphins, which cause feelings of happiness and increase pain tolerance. By contrast, chiropractic manipulates joints back into proper alignment so they stop pinching nerves, which causes pain.

“There’s strong evidence these practices help relieve musculoskeletal pain,” Mino says. “We feel offering these services appropriately is part of a comprehensive pain management program.”

That thought is shared by Nicholson, who was bedridden for years after her first bout with severe pain left her crying on the office floor. Acupuncture and physical therapy helped make the pain endurable, but on her worst days she relied on prescription painkillers.

“My experience with chronic pain was extreme. [Acupuncture] certainly helped a certain percentage,” she says. “Opioids are not a good solution for more moderate conditions.”

Eventually, a new surgery was able to remove the scar tissue on her spine, restoring her ability to walk. She still experiences pain, but through acupuncture, physical therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy, she’s able to push through it.

“Different things work for different people,” Nicholson says. “I think [insurance companies] should have the option where you get to try 10 visits to five different therapies so people can find what works for them.”

PREVENTING ABUSE

Employer-sponsored clinics — like the Nashville school district’s — are helping patients seek alternative treatments, while lowering opioid prescriptions. A recent study published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine found that employer-sponsored clinics prescribed opioids 2.8% of the time, compared to 20% at community clinics.

“We know that when patients have access to nonpharmacological approaches to treatment, opioid prescription is reduced,” says Dr. Daniel Lord, co-author of the study and senior program manager for Crossover Health.

Crossover Health provides employer-sponsored clinics with access to chiropractic care and acupuncture; their customers include large employers like Facebook, LinkedIn, Microsoft and Visa.

Last year, CVS-owned health insurance company Aetna rolled out features designed specifically to combat the opioid epidemic. Specifically, Aetna is encouraging its members to use chiropractic care, acupuncture, biofeedback and physical therapy coverage to manage chronic pain.

The company removed most precertification requirements for these therapies to make them more readily accessible to patients.

“We let the clinical evidence speak for itself; those treatments that have good supporting evidence, we’ll cover,” says Dr. Dan Knecht, vice president of health strategy at CVS Health.

Aetna also installed an educational program, in partnership with Alosa Health in Boston, where academic specialists visit primary care physicians in the five states most impacted by the opioid epidemic: Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Maine.

Knecht says these states are hit hardest by opioid addiction because of the prevalence of blue-collar jobs; workers are more likely to suffer work injuries and thus be prescribed opioids. This program hopes to change that by educating local doctors on pain management best practices.

“As a physician, from what I observed, physicians have often received inadequate training to treat pain,” Knecht says. “We need to make sure providers and physicians know there are other evidence-based treatments available that don’t include opioids.”

Knecht says a unique aspect of Aetna’s opioid prevention program is its Guardian Angel feature. After someone in Aetna’s system suffers from an opioid overdose, the insurance provider has a certified nurse or social worker reach out to the individual to provide support.

Aetna Guardian Angels have reached out to 600 patients — from teenagers to the elderly — since the program’s inception last year.

“These Guardian Angels call patients and find out what happened and how we can connect them to resources for addiction,” Knecht says. “They mostly want help navigating the healthcare system.”

Aetna representatives declined to name employer customers using the opioid addiction programs.

In his many years as a physician, Knecht witnessed the rise of the opioid epidemic in the 1990s, when doctors weren’t aware the pills were so addictive.

While he concedes “opioids have a place with cancer and end-of-life care,” Knecht says the statistics can’t be ignored — employers need to consider alternatives for pain management.

“I see patients suffering from the opioid epidemic all the time,” Knecht says. “Now that we’re aware of the risks of prescribing opioids, we need to be mindful of holistic approaches that are safer for managing chronic pain.”