February can feel like no man’s land. The holidays are over and the weather is crummy. The gentlest iPhone chime sounds like a bugle call in the morning and you need two Americanos to have a civil conversation. Over the past week or so, you’ve been holed up in your cramped apartment and your inbox is overflowing with alerts about the spread of a deadly virus. Like 84% of the population, you’re probably stressed, according to a recent study by Cigna and Asia Care Group.

The cost of burnout is no longer just emotional. The global economy loses

The good news is that there’s a solution, and it’s cheap. The bad news is that it’s difficult. After years of considering mental health to be a personal affliction, focus is turning to the role employers can play. The type of changes needed — better communication and support from managers, for example — require a shift in attitude more than financial resources. In Asia, however, the very

“My family never, ever talked about this topic. It’s a taboo,” said Deborah Seah, a 38-year-old Singaporean who lived with bipolar disorder for more than two decades before it was diagnosed. As a girl of eight, she recalls going to the kitchen of her family’s high-rise apartment in the middle of the night, looking out the 11-story window and fighting the urge to jump.

More than 90% of people in Asia say they’re stressed, and eight out of 10 feel like they operate in an “always on” culture. These can be early symptoms of burnout, which is marked by chronic exhaustion, cynicism and detachment from your work, as well as feelings of ineffectiveness.

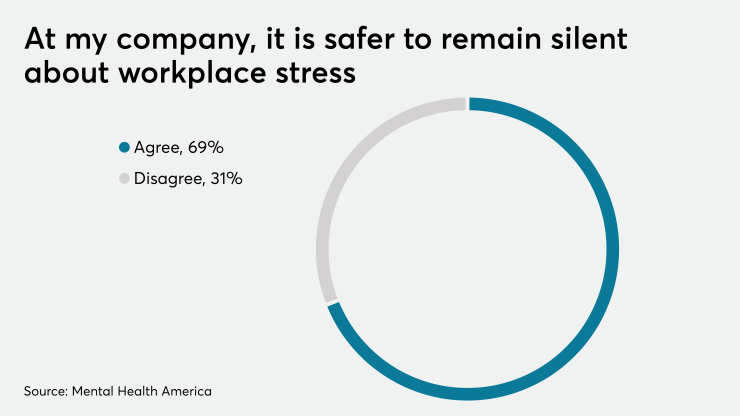

Seah experienced her first burnout episode in 2016, while working at an academic institution. She recalls the rising levels of stress as managers kept pushing work on her plate. She also felt pressure to keep her mental condition under wraps because colleagues gossiped viciously. Managers who knew of Seah’s struggles urged her to stay quiet.

Seah remembers breaking into sobs in the washroom, hoping no one would see, and coming home to dinner, where she would erupt into screams. Her husband begged her to quit her job, but she couldn’t let go: “I didn’t want to give up my career,” she said. Seah eventually admitted herself to Singapore’s mental-health institute when she began to feel suicidal. Successive burnout episodes were equally dramatic, with daily panic attacks, hot and cold flashes, uncontrollable shivering and the inability to get out of bed.

Beyond social stigmas, Asia’s often inflexible work culture can be a hurdle, too. In a recent survey of Hong Kong employees by Deacons, a law firm, 65% of respondents cited long hours as their primary concern, closely followed by “domineering” senior management and uncommunicative bosses.

The trouble is, even flexible work arrangements have their pitfalls. Ben, 43, started his career in public relations in London, and moved to Singapore in 2013. He struggled with depression and anxiety after his father and half-brother died unexpectedly within less than a year of each other. He was relieved to get a transfer to Hong Kong for a change of pace, and was initially encouraged by the corporatespeak about working from home and unlimited vacation time.

Very quickly, Ben found that working anywhere meant working all the time. He was pulling 12-hour days and putting in time on weekends; he compulsively checked his phone for messages. A much-anticipated trip with his wife to the tropical island of Flores, east of Bali, was spent on a deck chair: “I saw it over a laptop,” he recalls.

It also became apparent that making a big transition during a period of emotional strain was a bad idea. When Ben asked for help with his workload, his manager said he should be able to cope. As the demands increased, Ben’s symptoms became physical: He lost weight, his cheeks hollowed and his skin turned ashen. One day, he simply couldn’t get up, and stayed bedridden for a week.

Though Ben worked for a U.S.-based company, he felt caught between Asia’s cultural expectation of being in the office and the 24/7 demands of his industry. “When I was working in London, our general rule was if you saw someone working late regularly, you would take them aside and say, ‘Hey what’s going on? What’s wrong?’ whereas in Asia, it’s celebrated much more.”

Ben eventually decided to leave his job and took seven months off. Now he does contract work in the marketing-services industry, and tries to stick to a four-day week.

In 2018, Gallup, a market-research company, looked at the main causes of burnout, as well as what employers and

Seah, the Singaporean, eventually left her job, and now works as an executive assistant at Oracle. In her application, she included her volunteer work as an ambassador at “

The workplaces of the future should not only better equip its managers with soft skills, but give employees the time and space to care for themselves. Think about it: With people working well into their 70s, careers can plausibly span half a century; a recent study puts

For those who can’t afford to put their paychecks on pause, even mini breaks or meditation can help. One Singaporean-based app,

There’s perhaps no better time to put these tools to work. The spread of the coronavirus has produced stress triggers that are both extraordinary (with thousands of confirmed cases) and mundane (it’s more difficult to get your