U.S. workplaces have gotten a lot safer over the course of the past century. In 1913,

But those 5,250 deaths were an increase over 2017’s 5,147, and workplace fatalities have been up for six of the last nine years (the chart starts in 1992 because that’s when the BLS started its more-complete

Recessions tend to reduce the number of workplace injuries and deaths, because there are fewer workers to get hurt and because high-risk industries such as construction and trucking are often hit hardest by job losses. Some increase in fatalities was thus to be expected as the economy recovered in recent years, and the current number and rate of fatalities remain below the levels that prevailed before the last recession. (The BLS changed how it calculated the rates in 2006, which is why this chart only goes back that far.)

There was, however, something unusual going on in 2006 — a housing bubble that pushed the fatality-prone construction sector to its highest share of nonfarm employment since 1956 — that makes the drop afterward less impressive and the subsequent failure of the fatality rate to keep falling the bigger story. It is also possible to identify a major force that has been keeping the rate from falling. This force is not necessarily evil, but as a 56-year-old I do find it kind of creepy: More people older than 55 are working, and people over 55 are more likely to die on the job than younger workers.

First, the statistics on 55-plussers in the workplace:

This rise of the older worker is partly just demographics — the giant baby boom generation,

Older Americans are likelier to be working now for a variety of reasons. Some seem entirely positive — despite the recent stall in life expectancy, Americans

In any case, as the share of older workers has grown, the share of workplace deaths that they account for has grown, too.

It’s not that the workplace has been getting more dangerous over time for older workers. Every age group has seen declines in workplace fatality rates since 2006, and the decline for those 65 and older has been the biggest. But 65-plussers’ share of the workforce has grown by three percentage points just since 2006, and their occupational fatality rate remains much, much higher than anybody else’s: 10.3 in 2018 versus 3.5 for the workforce overall and 4.6 for those ages 55 through 64.

Being older obviously does make one more prone to keel over, but the occupational fatality statistics don’t include on-the-job deaths due to natural causes. So what explains the higher death rates of older workers? In

One thing that they found was that those 55 and older were more likely than younger workers to die of lingering injuries days, weeks, months or even years after a workplace incident. Older people are more fragile than younger ones, so they have more trouble recovering from workplace injuries than their younger peers, and are more likely to suffer certain injuries (hip fractures, for example).

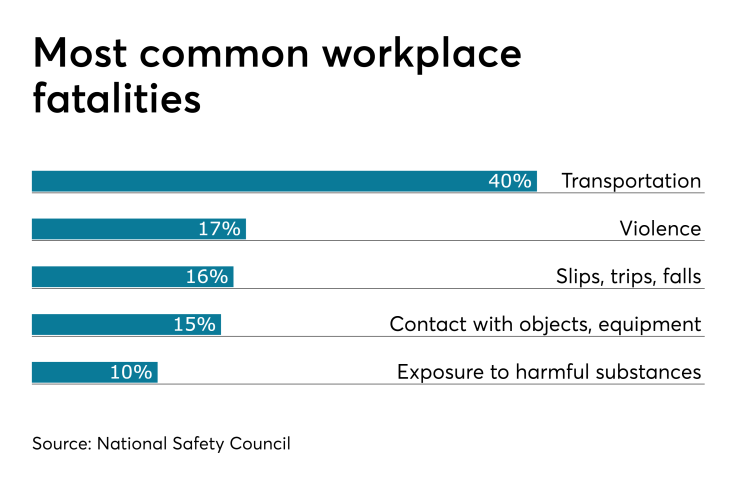

When it comes kinds of accidents, the biggest cause of workplace fatalities for both older and younger workers is

What could these nonroadway noncollision incidents possibly involve? Think tractors. Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting had the second-highest fatality rate in 2018 of any industry whose fatality rate was estimated by the BLS, after truck transportation (23 deaths per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers versus 28). Smith and Pegula found that, from 2003 through 2017, farmers, ranchers and other agricultural managers suffered 14% of the occupational fatalities among those 55 and older, versus a bit more than 2% among those 54 and younger.

For a

Which brings us to the bigger question of whether anything should be done about this rise in older-worker fatalities. Smith and Pegula conclude their study with the hope that it will help safety and health experts “tailor their efforts to best meet the needs of older workers and to keep them safe during their careers,” which sounds like a good plan but not exactly a game-changer. Technological advances have played a big role in reducing workplace risks in the past, and one can easily see how self-driving technology could make truck driving, farming and other occupations much safer — albeit at the same time destroying lots of jobs. In the meantime, the most powerful policy lever seems to be retirement-system design.

In countries where old-style pensions still prevail, 65-plussers are

This would also, of course, be very expensive, and