At a time of high 401(k) fees, traditional pensions facing extinction and mounting concern about the nation's retirement readiness, a newer style cash balance plan could breathe life into so-called hybrid retirement savings vehicles.

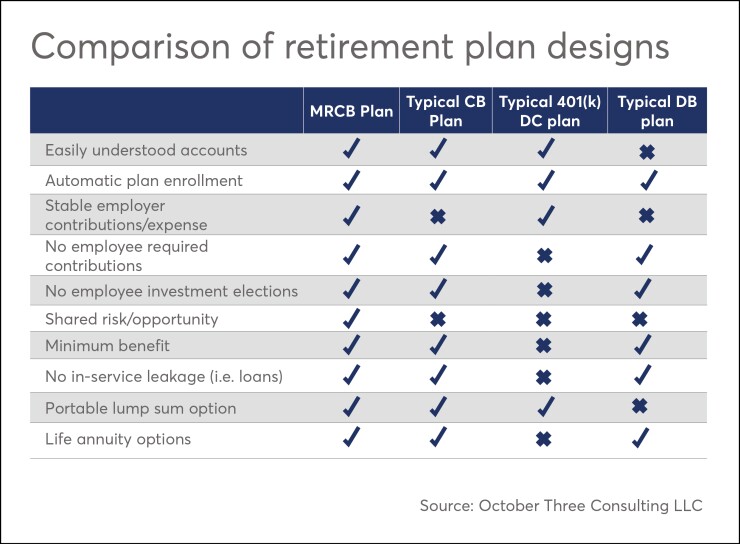

Market-return cash balance plans may represent the best possible compromise for employers and advisers who are leery of embracing a solution associated with defined benefit plans, which are facing extinction. These plans more closely resemble the DC model than traditional cash balance plans, which first merged DC and DB plan elements more than 30 years ago. Given this fact, they could be seen as a more realistic alternative to a languishing system.

“We feel strongly that a defined contribution plan as a stand-alone, core retirement vehicle just doesn’t get the job done,” explains Larry Sher, a partner at October Three LLC, an actuarial, consulting and technology firm that seeks to revive interest in DB and hybrid plans. “Our feeling is that this kind of design, together with a defined contribution plan, as a package makes more sense from everybody’s perspective, including the employer, employee and government.”

Given the tendency to freeze not only defined benefit plans, but even cash balance plans, Sher says, plan sponsors have hesitated “to move in a direction that is counter to where the herd is moving.” The same goes for advisers, Sher notes, who have “a sense of resignation at most of the firms about any kind of defined benefit plan.”

However, he encourages brokers and advisers to keep an open mind about promoting hybrid retirement plans on behalf of their employer clients. And while the government can still do more to help advance these plans by offering additional regulatory clarity, he believes consultants could play a significant role in turning the tide.

Two types of stories dominated the attention of the Employee Benefit Adviser's audience in 2016: the details hidden inside benefit plans and how to implement them.

While the Pension Protection Act of 2006 helped pave the way for more market-return cash balance plans, Sher says it then took nine years for regulators to finalize guidance for plan sponsors. The few dozen of these next-generation cash balance plans that existed prior to the PPA had a more questionable legal status than their traditional brethren. Since that time, he says, many smaller companies and law firms have adopted this design.

The key distinction between a traditional cash balance plan and a market-return cash balance plan is in the way interest is credited, Sher explains. While the former uses a bond or treasury rate that tends to change once a year, the latter is tied to a real investment return on the plan’s own assets, a subset of those assets, or outside source such as an S&P 500 mutual fund or a combination of mutual funds.

Apart from a preservation-of-capital minimum funding level that must be met, there’s also a cumulative rate of return that can be up to 3%, but can’t actually be negative. He says a “floor of protection” under the law would make the sum of those pay credits at least zero.

What this means for market-return cash balance plan sponsors is that they can provide participants with some “downside protection” and “upside opportunity” in terms of investment returns, according to Sher.

He also touts the potential for greater flexibility. “A cash balance plan might be able to act and be designed like a target date fund,” Sher says. “But at the end of the day, the DC plan really is designed much better for supplemental and short-term savings, whereas in a cash balance plan, just like any DB plan, once benefits are accruing, you don’t have loans or in-service withdrawals.”

Since the investment risk is mostly borne by employees in many of these newer designs, he says, employers reap the benefits of “more cost stability and control,” as well as “predicting the accounting and contribution amounts even better than a traditional plan.”

The market-return approach to cash balance plans, while seen as intriguing, isn’t necessarily a panacea. Ted Benna, a veteran industry observer commonly referred to as the “father of 401(k),” welcomes creative alternatives, but adds some caveats.

“I don’t think the current defined benefit system is the answer because it has and always will be badly underfunded,” he cautions. “If I were CFO of a company that still had a defined benefit plan, an immediate goal would be to terminate the plan ASAP before the next bear market, rather than seeking a new design that would tie my company more deeply into this systematically underfunded system.

“Most employers that adopted cash balance plans have discovered they haven’t solved their pension problems,” Benna adds. “Therefore, I suspect they will be reluctant to embrace a new model.”

The bottom line, says Benna, who is writing a new book that tracks the history of 401(k) fees, “is that employers need to properly manage their 401(k) fees.”