Early adopters of state-run retirement plans are calling other states to follow suit and start rolling out some variation of a model that offers workers a savings plan when none is available through their employer.

Oregon was the first state to get its retirement plan up and running, and the official who leads that program is hoping that the model will take off as other states grapple with the challenge of getting more workers to save for retirement.

"While we work in the state of Oregon, we know that this is a movement," Michael Parker, executive director of the Oregon Savings Network, said at a recent event hosted by Georgetown University's Center for Retirement Initiatives. “We want to be part of that movement; we really want to get it out there.”

"We want to do everything in Oregon to make sure that other states have this opportunity," Parker said.

More than 40 states have introduced proposals to set up some kind of public option for retirement savings, according to the Georgetown center, which has been tracking those efforts. To date, 10 states and one city (Seattle) have set up their programs, and three states are actively enrolling workers.

For plan advisers, those state-run programs can be a mixed bag. On the one hand, driving up enrollment in retirement plans could create new opportunities for advisers. However, some industry groups such as the National Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors worry that the government plans will be in direct competition with private offerings, and are opposing state-run plans. State officials, for their part, reject the notion that their plans are a threat to the private sector, arguing that their singular goal is to get more people to save, and if that happens through more attractive private plans, so much the better.

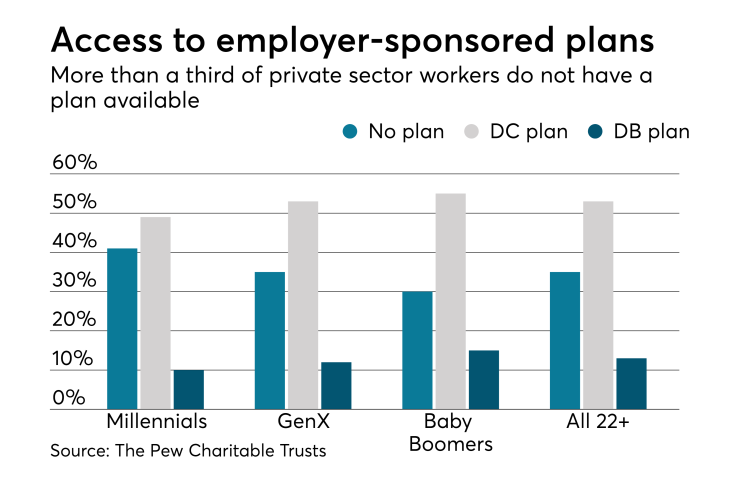

The programs vary in details such as which businesses will be compelled to offer workers a state-run plan or a satisfactory private alternative, but all come in response to the concern that too many Americans aren't saving enough for retirement, and that the most effective way to encourage them to put money away is through a plan at work.

In Oregon, officials are gradually phasing in the program, but by 2020, every business in the state will be required to automatically enroll workers in the OregonSaves program or some other qualifying plan.

California and Illinois have their own plans coming online this year, each poised for a gradual rollout through which they hope to strengthen the retirement safety net.

"This is [a] pretty major cultural shift that we are all setting out collectively to effectuate, and it's going to take time," said Katie Selenski, executive director of the CalSavers program. "We're trying to reach double digits millions of people and really shift the paradigm of how people think about their financial lives both employers and employees."

Experts have

In Oregon, Parker is positioning his program not only as a model for other states to follow, but opening the door for other states to come in as partners and use some of the infrastructure that his office has built to get their own plans up and running.

"[I]f there are states out there who necessarily don't have the means, the resources, the human capital to start one of these programs, but would like to do it in their state, we do offer some kind of collaboration where states can come on, essentially have a program that just operates off the Oregon rails," Parker said. "We're going to be very successful around the country if as many folks as possible are taking advantage of these programs."