When Steven Daigle, a regional senior vice president at Bank of America in Boca Raton, Florida, became a father of four in 2017, he was given time off to care for his newborn twins, Providence and Joshua. After the birth, his wife Kim stayed home the first six months, and Steven took the next four, which allowed them to keep the twins out of daycare for the first 10 months of their lives.

“My parental leave was an amazing opportunity to step away from the day job and focus on bonding with and caring for my 6-month-old twins,” Daigle says. “From the feeding routine, to daily walks or changing diapers — I enjoyed every minute of getting to know my children during this important time in their lives.”

Steven had paid leave, but his wife, who works for another company, had to take time away from work that was not paid.

“It is absolutely critical that [my time off] was paid,” he says. “To not have that financial stress while we were caring for the twins made all the difference in the world.”

Daigle is just one Bank of America employee who has benefitted from the company’s 16-week paid parental leave policy, which went into effect in 2016. In fact, Bank of America says the policy has helped drive employee satisfaction with benefits to an all-time high.

Each year, the company measures growth and employee satisfaction through an employee engagement survey, which has increased over the last several years.

“Our satisfaction with benefits are basically running at an all-time high,” says Chris Fabro, global head of compensation and benefits at Bank of America. “It is certainly helping drive our ability to keep teammates in the bank and help them grow their careers here, so we see less turnover.”

Although Bank of America has provided their employees with paid parental leave for decades, the company chose to extend its benefit from 12 to 16 weeks in 2016. The policy is gender-neutral, and the company doesn’t differentiate between primary and secondary caregivers.

“We want to see both moms and dads actively engaged in the parental process,” Fabro says. “We think it’s important for all teammates to take time away and really come back recharged and engaged and feeling good about themselves and their families. Because when they do that, they return to work even more committed than they were before.”

See also:

Although parental leave is a hot industry trend, research has shown that men are less likely to take leave and they take it for shorter periods. Many companies are still trying to figure out how to get new fathers to take time off, which is why Bank of America says it tries to make sure that fathers actually use the parental leave benefit.

“There’s been a stigma in cultures where, for whatever reason, caregiving responsibilities has tended to fall more toward females, and we want to make it clear that dads can play an important part in that too,” Fabro says.

“We think this is important. Our employees all have different lives and unique responsibilities, so we give our employees the flexibility to choose when they take that time off,” he says.

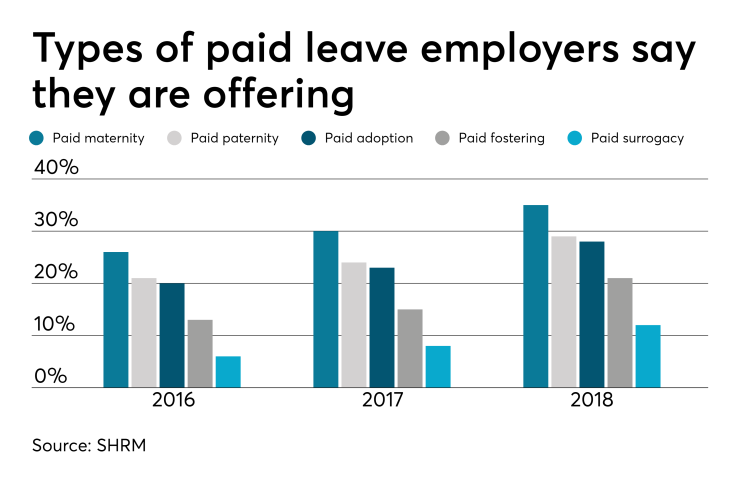

The number of employers offering paid parental leave benefits jumped to 27% in 2018 from 17% in 2016, according to the Society for Human Resource Management. Companies are increasingly recognizing time off for new parents as a competitive edge in recruitment, as well as a way to increase employee productivity and retention.

“[Not offering employees parental leave] is not sustainable; [there has to be] support for these huge life events. I mean, you have to recover after having a child and you have to bond with the baby,” says Jennifer Allyn, diversity strategy leader at Firm PwC. “It’s about work-life integration, so that employees can achieve all of their goals and be more satisfied, and then ultimately more productive.”

More companies may be offering paid paternity leave to their employees, but it is still far from being a standard in the benefit industry. The United States does not have any federal laws mandating paid parental leave, although the Family and Medical Leave Act provides certain employees with up to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave per year.

A few states, including Washington and California, have also passed local paid family leave laws. In California, a study found that its paid leave law increased women’s labor force attachment in the months surrounding a birth. Research on the long-term employment consequences of state paid leave programs is not yet available, but an increase in short-term attachment is likely to translate into long-term employment gains, another analysis found.

See also:

Bank of America is supportive of federal efforts to create national leave laws, including parental leave, Fabro says. The current patchwork of parental leave ordinances, that can vary by state and local laws, makes communicating and administering benefits challenging, he says.

“At 16 weeks, we’re above all those minimums, but it does present a challenge,” he says. “Any progress to help improve consistency or set guidelines that reduce complexity for employers and managers of having to administer such a wide range of different plans and different places, that’s a positive.”