The fiduciary rule and President Donald Trump’s tax reform efforts were the big topics addressed Sunday during the opening of the NAPA 401(k) Summit. But the big takeaway for employers is that tax reform may inhibit employees’ ability to save for retirement.

“There are people in Washington who do not understand the relative importance of retirement savings plans,” said American Retirement Association CEO Brian Graff, who noted that he has never seen this level of federal activity surrounding retirement issues before.

“Things are changing on an hourly basis. … I have anxiety from what’s going on and how it will affect our industry,” he said, noting a big concern is tax reform proposals that might cut 401(k) contribution limits.

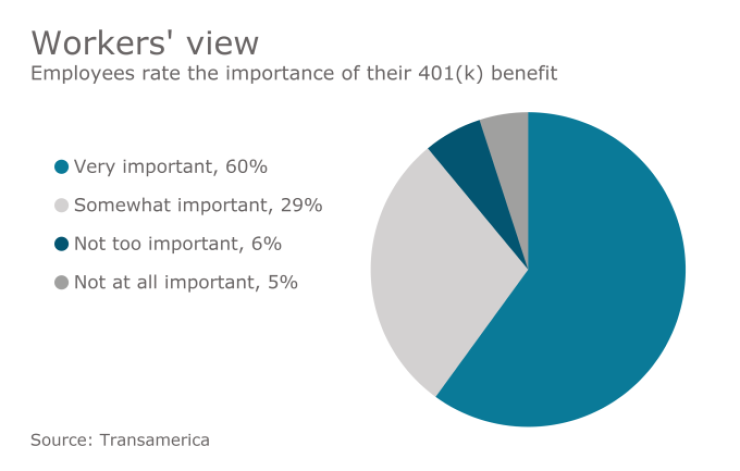

“Why would Congress want to cut 401(k) limits if they are concerned about people not saving enough for retirement?” Graff asked. Consumers are 15 times more likely to save for retirement if they have a plan at work than if they don’t, he said.

“It’s impossible to do tax reform without winners and losers,” said Graff. “If they do tax reform, there is no chance — no pathway — that we get through it unscathed. We might think it’s crazy to reduce 401(k) limits, but you have to understand, in the context of tax reform, everything is about tradeoffs. Tax reform is an exercise in making choices.”

But it’s not all dire news for the retirement industry, he said. There is some progress being made. Legislators are beginning to realize that cutting savings incentives for employees is not good for economic growth; they also are cognizant of the political consequences of tax incentives that primarily benefit those with high incomes.

Fiduciary rule

The DOL’s fiduciary rule has been a longstanding point of contention both for retirement advisers and plan sponsors. The good news, noted Brad Campbell, partner at Drinker Biddle & Reath and former assistant secretary of labor for Employee Benefits, is that the Trump administration seems “very sincere” about delaying the rule. The president announced the delay March 1.

See also:

The problem, Campbell said, is though the 60-day delay of the rule was a good start, it wasn’t good enough.

“Sixty days isn’t long enough, except to avoid a calamity,” Campbell said. “You need to have some certainty. Sixty days is only long enough to avoid an immediate problem but isn’t long enough for anything else.” That timeframe only gives the administration enough time to look at comments about the law, he said — not to rewrite the law or figure out the next steps.

Still, he added, the Trump administration is correct in trying to figure out “what the effect of the rule would be” by determining if real-world experience is proving that the rule was unnecessary in the first place.

Comments from retirement plan sponsors and advisers to the DOL is “vital in getting the rule changed — they have to justify that … the rule was done wrong and why.”

The biggest concern right now, Campbell and Graff agreed, is the possibility of a so-called “gap period” in which the industry starts complying with the rule only, to have changes made later. That, Campbell said, “would be a problem of Biblical proportions.”

And, Graff cautioned, stopping the rule is not as simple as it may seem.

“There is no button they can press” to stop the rule, he said. “The regulation is law.” The only way to do it, Graff said, is to put a regulation in place. But that entails economic and regulatory analysis, which “almost certainly” some consumer groups would challenge in court.

“There is definitely a way to fix this, but it’s going to take time,” Campbell added.